The Johari Window can be one of many powerful tools for crafting dimensional characters. It can also help creators develop layered stories (plots) that will resonate long after the audience reaches “The End.” Why?

Because great fiction is even better therapy. And after the past four years in particular, who DOESN’T need at least a little lot of therapy?

Yes, I’ve talked about the Johari Window before, but it’s been ages. Since I figured most of us have slept since 2021, it seemed like a fantastic topic to start off the year (especially for those who’ve set a resolution to write a book…preferably a GOOD book).

Too many believe fiction to be a fluff, an escape, a fantasy getaway (while, ironically, spending almost all disposable income consuming it).

Some fiction does this for sure. Yet, the stories that hit the market and continue to ripple for decades, centuries, or even for millennia share a common denominator.

Stories offer the audience deeper insights into themselves, their beliefs, and the world around them. It trains empathy and gives us the easiest way to “walk a mile in another person’s shoes.”

Additionally, great stories have timeless messages. It’s why we can take a Shakespearian play and set it in modern times and the story and message are just as powerful.

The characters might wear modern clothing, fight with machine guns instead of swords, but we identify with their hopes, dreams, hurts, struggles, blind spots and weaknesses just as much as the audiences from centuries ago.

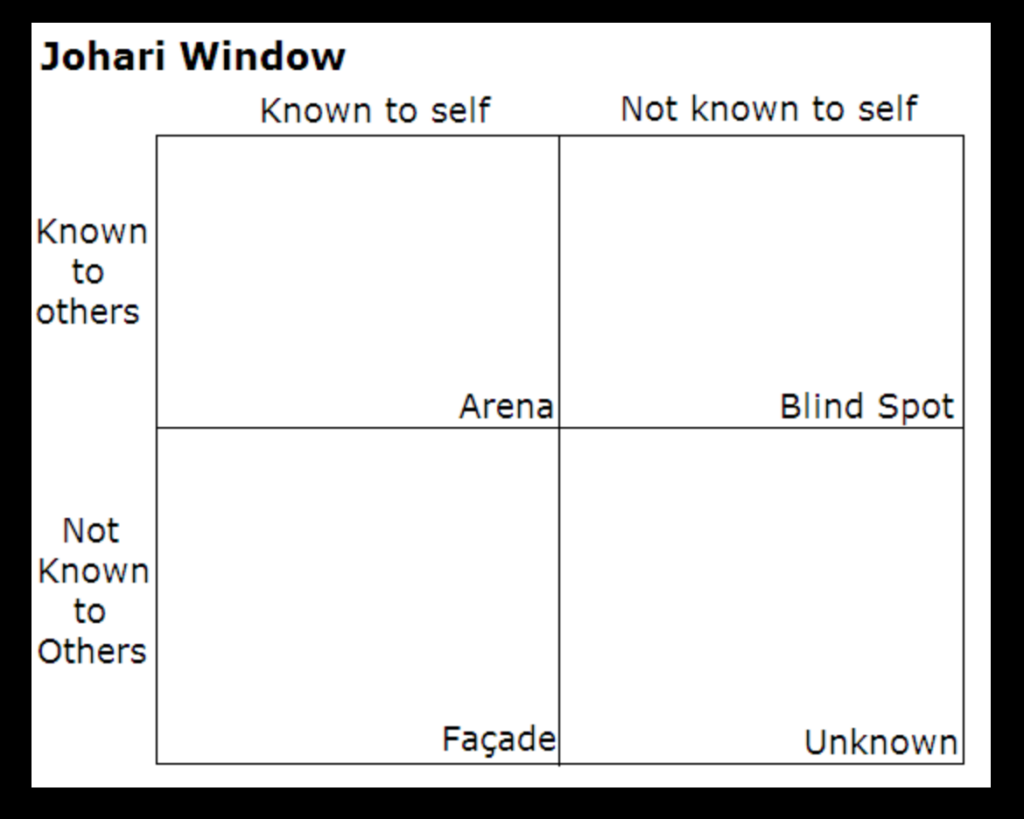

What is the Johari Window?

American psychologists Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham developed this model in 1955 as a way to improve group dynamics. The Johari Window is a technique used to refine and boost feedback, prompt disclosure, and ultimately deepen self-awareness.

“Johari Window” derived its appellation using a combination of the two psychologists’ names.

The model is founded on two fundamental ideas.

First, that trust is earned when one reveals personal information to others.

Second, that this information then leads to feedback from others which can then give the person a more accurate “reality.”

Using feedback, we can become more self-aware and change accordingly.

The Johari Window Structure

The Johari Window consists of four “panes.” Two panes reflect the self and the other two represent blind spots and areas unknown to the self but visible to others.

The first pane is the most open. This is information a person knows that others know as well.

The second pane is the blind spot. Often this is what others can see, that the person (character) cannot.

The third pane is a hidden area containing information the person knows, but hides from others.

The fourth pane is the Unknown area, the place where all parties are completely in the dark.

Creating a Character

The blind spot is critical for creating a dimensional protagonist who can arc to becoming a hero. Ideally, we want to design a story problem that forces the MC (main character) to finally see their blind spot and how it’s negatively impacting their lives (and others).

The story problem is the crucible. If our MC had never encountered the story problem, they would have remained ignorant of a critical weakness.

Other characters in the story (mentors, allies, antagonists) represent the sounding board that drives that final self-awareness and group understanding.

Ideally, by the end of the story, the MC has dealt with the blind spot, and the Unknown Quadrant will be markedly smaller.

Applying the Johari Window for Fiction

Now that I’ve explained what the Johari Window IS, how can we apply it practically if we don’t work in HR?

Instead of using a movie or book, I’ll riff a quick example. It’s rough and imperfect but most novels are in the beginning. The key is that we at least get off to a sound start with a solid story foundation.

Let’s say I want to write a Young Adult Urban Fantasy about a teenage girl, who, after a bad accident, starts having nightmarish hallucinations.

She’s unaware that she can actually see into the future.

Pane #1

This is information my character knows mixed with what others also know. This is usually very surface.

For instance, the character, her fellow students and teachers know her name is Sarah Smart, that she has lank dark hair and is spindly thin. She’s a sophomore at Small Town High who performs just well enough to pass her classes.

Sarah is a loner who sports combat boots, spiky jewelry, and concert shirts from various heavy metal bands.

She doesn’t have friends, lives in a rundown area of town, and rarely talks to anyone. Though she doesn’t cause trouble, she goes to great lengths to push people away. Perhaps she answers any questions with closed-ended, yes-no answers.

Maybe she cuts class, or retreats to the library whenever there’s a pep rally. She also constantly chews aspirin.

All this “information” is obvious to Sarah and those around her.

Pane #2

This is Sarah’s blind spot. Others might see areas of the blind spot, but Sarah will be oblivious.

Sarah fails to see herself the way others do. In her mind, she’s not hurting anyone and wants to be left alone. Others, however, find her caustic, abrasive, stuck up, or just plain weird.

Sarah thinks she’s crazy, her headaches and visions a remnant from a head injury suffered in a bad car accident.

Pane #3

This is what Sarah knows that others do not.

Her mother who, after almost twenty years sober, now drinks every waking hour. Mom fell apart after her only son (Sarah’s brother) drove the family car headlong into a tree and died.

The tox screen indicated he was well over the legal drinking limit. Also, witnesses claimed to have seen him swerving and driving erratically, thus the town rumor was that he was driving under the influence.

His body was so mangled, Sarah and her mom had to hold a closed casket funeral.

The town gossip grew so bad, Sarah and her mother had to move. No one in the new town or school knows about her brother, the accident, or her mother’s severe drinking problem.

Right after the hospital released Sarah, she suddenly started getting bad headaches coupled with terrible and confusing visions. She has no idea what’s happening and believes she might be going crazy.

Perhaps, she believes the headaches are from the accident, the visions are due to her guilt. Why did she let her brother drive? Why did she not see he was unfit to drive?

She hadn’t even seen him drinking. He hated alcohol because of what it had done to their parents. But the tox screens don’t lie, right?

His death is all her fault and these headaches and nightmarish visions are her due punishment.

Pane #4

This is the information unknown to all parties involved (at least in the beginning). Sarah isn’t going crazy, she actually has the ability to see into the future.

Her brother wasn’t drunk at all. He, too, had the same gift—he could see into the future—and was hit with a vision while driving which caused him to lose control of the car.

This is also what will form the basis for the story problem (more on that in a moment).

Sarah actually wants friends, to be part of a community, but is too ashamed and afraid. The story problem will change this and shrink the Unknown for Sarah as well as those around her.

Story Problem

Using this quick exercise with the Johari Window, it’s now easier to construct a story that will force Sarah to face what she fears (that she’s going crazy) and to make peace with her inner demons (guilt about brother’s death).

Ideally, it will drive Sarah onto a path where she’ll gain mentors and allies. The more awareness she gains, the more information she shares, the closer relationships she will form.

Story Problem: What if Sarah’s brother actually is NOT dead?

If we take a page from to hit Netflix series Stranger Things, maybe some black bag government operation had been watching her brother.

He’d been in counseling, discussing his visions and someone with a lot of power realized they weren’t hallucinations at all. Rather, the young man could actually see future events.

At the time of the accident, this agency saw the perfect opportunity to abduct the brother. They substituted another (badly mangled) body, forged the tox screen and dental record match, then helped spread rumors the young man died drinking and driving.

This agency is now using him in some underground bunker to predict terrorist attacks.

Normal World

We get to know Sarah in her regular, but broken, world. See her picking up empty bottles of cheap vodka and putting her mom to bed before she heads off to school. Maybe she prizes a photograph of her “dead” brother out of Mom’s hands as she tucks her in to sleep off the booze.

At school, Sarah sits on the sidelines wanting to be part of the group, but pushing away anyone who tries to be friendly. Maybe she runs into a new substitute teacher who sets off all her spidey senses, but she has no idea why (he’s an agent following to see if Sarah, too has the gift).

The substitute teacher is a proxy, and how we introduce the Big Boss Troublemaker—the black bag agency that has her brother hostage and wants her, too.

Sarah later talks to a teacher, only to have to cut the conversation short because of one of her headaches. In the bathroom she’s knocked to her knees with a vision of a fellow student run over by a jock speeding through the parking lot, but dismisses it.

Only a nightmare. A hallucination.

She firmly believes this until she’s leaving school and the leading action preceding up to the event plays out exactly as she’d seen it happen in her vision.

This time is different. She takes action.

Sarah dives after the kid, preventing them from being run over. The fellow student likely will be her first ally.

Yet, her direct intervention into a future event will also be the signal that lets the enemy know Sarah does have the gift they seek.

This is a turning point for the BBT—she’s like her brother and they want her, too. It’s also a turning point for Sarah—maybe she isn’t crazy after all.

Plotting from the Panes Pains

See how using the Johari Window we’ve created a dimensional character with a lot of baggage, issues and self-doubt? This knowledge also offered a clear way of seeing a solid story problem that would make Sarah grow.

Also see how the plot practically FALLS into place?

What would our Sarah want more than anything? To have her brother back.

If she starts suspecting she isn’t crazy, this propels her on a search that will begin revealing that she actually does see the future, her brother had the same complaints, and if he had her gift? Maybe he isn’t dead.

She’s propelled down a path searching for answers, a road that will inevitably lead to finding out the truth.

We also have an accurate picture of her in her community in the beginning and a good map of where the story needs to go.

If it begins with Sarah as a loner, wracked with guilt and shame and alone?

Then it should end with the family restored and those responsible for taking her brother defeated.

She also won’t do this all alone because as she grows, gains feedback, and information flows freely, the Unknown—there is a secret agency that abducted her brother—shrinks significantly.

Sarah, freed from false guilt and shame, should be a far different person at the end.

Also, those around her, will see her with different eyes.

Sarah isn’t some weirdo jerk with a chip on her shoulder. She’s their friend, ally and she has very special powers. The entire group has new knowledge, which creates a powerful and unique bond.

There really IS a world of black bag operations, underground bunkers and dangerous men in suits willing to do anything, even kill, in order to abduct teens with special abilities to use or weaponize.

The Johari Window Story as Therapy

Most good fiction is a journey to self awareness. We have a protagonist in his/her normal world. Everything is fine…but not really.

There is a critical missing piece keeping the protagonist from being self-actualized. This is plainer to see when we realize that most beginnings and endings of novels (and movies/series) are actually bookends.

Normal world is their world with the wound festering and hidden. The denouement? The world is restored but whole, wounds exposed to heal.

All of us have blind spots. If we didn’t, therapists would go bankrupt and have to get a “real job.” Truth is, most therapists know exactly what our problem is the first day we sit in their office. Problem is there are all kinds of other emotions clouding our vision.

This is one of the reasons shrinks do a lot of listening, nodding and asking questions. And probably a lot of doodling and playing tic-tac-toe on their notepads to stave off the boredom while they wait for us to catch up to the obvious.

Our story problem in a sense is extreme therapy for the protagonist. Instead of our character spending years on a couch being probed with uncomfortable questions and given homework to write letters to her inner child?

She is thrust into a bank heist, an alien invasion…or her brother is abducted because he has visions of the future that others want to use for their own ends.

The “Johari Window” as Writing Tool

There are countless methods for creating a cast of dimensional characters. Yes, it is a therapy technique as well as a tool to improve communication. It is also AMAZING for crafting plots and characters (unreliable narrators especially).

But, I hope my example above showed you how you might employ the four panes to craft deeper, more layered characters. How it can also help us make sure we’re choosing the best story problem that will drive the most change.

What are your thoughts on the Johari Window? I LOVE hearing from you?

Had you ever heard of the Johari Window? Are you eager to give it a try? I’d only tinkered with the concept mentally until I wrote this post, but I was able to create a character and a pretty decent plot problem in about an hour.

I’d love to hear from anyone who tries this and your results! Or if you’ve used it before and how it worked out. I know it’s a rather odd leap from a tool used by many companies as more of an HR tool, but writers are masters of repurposing 😀 .

16 comments

1 ping

Skip to comment form

I really appreciate your sharing the Johari Window concept. I definitely see the possibilities this concept opens for stories in my future. Thank you Kristin

Fascinating and very helpful for character development! Thank you

!

Fantastic advice!

Another interesting blog, Kristen. So can we expect a YA urban fantasy from you?

First time I’ve heard of this. What a great tool for character and plot development. A big fat thank you.

I’ve actually, unwittingly, been using this concept to some degree and it works for the very complicated novel. Now that you’ve elucidated what I was doing naturally, it will make the final product all the better. Thank you Kristen!

This is very insightful! The whole time I was reading, I was recognizing how traumatic events in life forced me and people in my life to change. I also see that my MCs are completely transformed from the first pages to the end of my book. Thank you for explaining it and even writing an intriguing story. ? I love reading your posts!

(Hmmm … the ? was a smiley. I guess I can’t use emojis in my comments.)

Author

I figured that out a while back in the comments so I know the ? is a smiley. Much appreciated.

Great post, explaining a really useful tool – I’d never thought of using it for character development, or even for story plotting. Thanks!

This is one of the best posts I’ve read in a long time. Your explanation is clear. I will be using this for my next WIP.

Author

SWEET! Let me know how it goes!

Kristen, I was going to write to you awhile ago when you wrote the very personal posts about being on the spectrum. If you have any doubt in your mind about how people are now perceiving you, let me assure you that I (and I’m sure many others) think you’re terrific – your ideas, your phraseology, your humor, your wisdom, you are the best YOU can be and that is damn good!

Author

That means a lot. Thank you, and I very much mean it. (((HUGS)))

The Johari window concept in writing is an excellent perspective. I’ve used it in business and now, combining these two concepts opens possibilities! Thanks!

Author

I look forward to hearing your results!

[…] The Johari Window & Character Blind Spots by Kristen Lamb […]