Motive is a key ingredient that differentiates stories that sizzle versus stories that fizzle, namely because we all want to know ‘WHY?’.

Why does a character want this or that? What drives them? Who would do such a thing? How did a character become a certain way? Can a character change?

A character’s central motive is the key that unlocks our interest. It’s less about what a character is doing or not doing and more about WHY. If we (the audience) don’t understand or can’t relate to a character’s motivation?

We can’t care.

This is why ‘white hat’ and ‘black hat’ characters are so dull. Humans can’t authentically connect to ‘wholly noble’ or ‘wholly evil’ characters who are for good simply because it’s ‘right’ or or evil ‘just because.’

Regardless what any character wants to achieve—or conversely, wants to avoid at all cost—we (readers) must understand and be able to empathize the underlying motive driving their choices.

Fiction, at its most fundamental level is always cause and effect. We can’t have effects without causes and if we do? Readers will call FOUL.

Don’t believe me? Read my blog about the train wreck commonly known as Game of Thrones‘ Season Eight.

Some Sizzle While Others Fizzle

What makes one book a staple in our library but renders others utterly forgettable? Some books, I can’t recall if I even read them.

In fact, bizarrely enough, sometimes I’ll look at my Kindle/Audible menus and my devices will claim I’ve read or listened the book(s) to completion but…

Other books I read over and over. I still revisit A Girl on the Train, Gone Girl, The Luckiest Girl Alive, Dune, What Alice Forgot, Fahrenheit 451, and Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and others because I learn (and see) something new with every pass.

This said, we’ve been talking a lot lately about character/character creation. So, I returned to my favorite books and did some reverse engineering in hopes I might better understand what made the critical difference.

What’s the Character’s Paradigm?

This is to say, what is her reality? Her framework? How does the character define herself? Does he define himself via internal or external factors or both? How accurate is his self-image?

What forms the character’s center? How does the character define his or her worth? What’s the character’s central motive?

We must ask and answer all these questions because, without those answers, a background sheet is nothing more than facts devoid of context. And, to create a dimensional character, context is king.

Paradigms offer context.

For instance, Dr. Gregory House (image above) saves lives. He solves unsolvable cases for patients who, without his help, would be dead. But Dr. House IS Dr. House because of his driving motive.

Patients are puzzles not people.

Same end result—the patient is cured—very different motive. Dr. House is no soft touch with a tender spot for the suffering. In fact, he’s borderline sociopathic which is why his character was so complex.

Bad Decisions Make Excellent Stories

Great fiction is about problems. It is about people with problems. Stories are about a wholly wrong motives that eventually lead to deeper understanding, personal growth, and ultimately better motives.

And the more messed up our characters are? The more we have to work with 😀 .

This means that, to write any great story, we need to create some seriously jacked up people. To do this, we need to know the character’s paradigm. But before we go further, I want to explain a bit how a paradigm works.

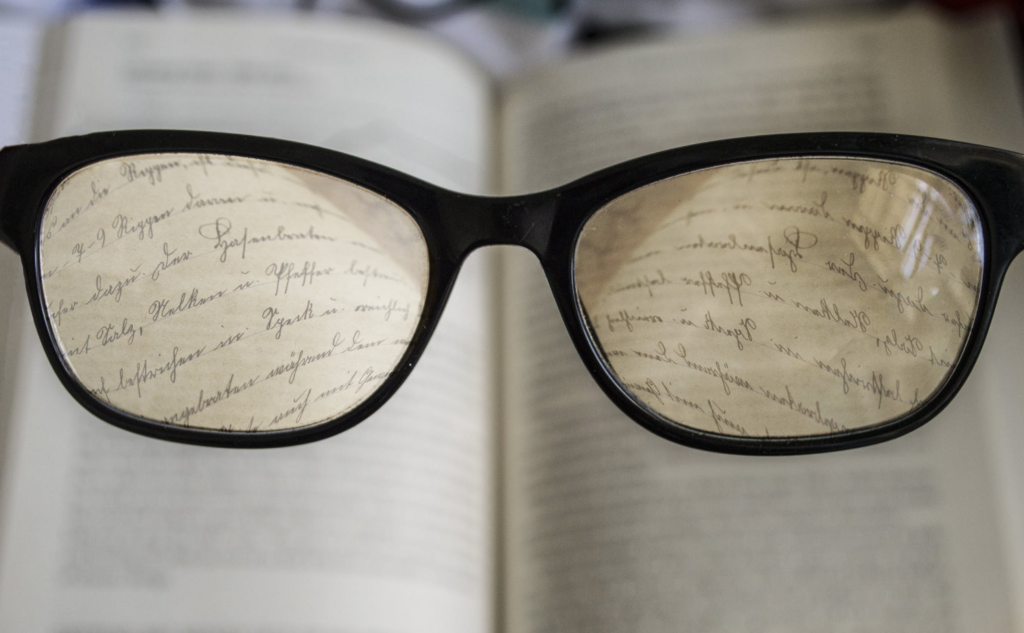

Stephen Covey’s book Seven Habits of Highly Successful People, explains the paradigm as a set of lenses through which we see ourselves and our world. A great concept for self-help, but also a fantastic tool for building characters that resonate with audiences.

Rolling with the ‘lenses’ metaphor…

A Tale of Two Paradigms

When I was pregnant with Spawn I suddenly needed glasses after having perfect vision my whole life. After he was born, I kept wearing glasses, assuming the change was permanent.

But then something strange happened.

When Spawn was about three I started getting really bad headaches. My eyes hurt. I couldn’t see detail. Naturally, I assumed I needed a stronger prescription because I was getting older. I went to the eye doctor who told me the best way to correct my vision was…

…to stop wearing my glasses.

The glasses were giving me the headaches because my vision—after the hormones settled down—had returned to 20/10. I’d been wearing glasses simply because they’d once worked and I’d been wearing them so long I was supposed to need glasses.

Right?

When creating your character, take all of that background information then go deeper and reflect on what lenses the character is using. What’s impacting their core motive? False guilt? Shame? Bad or outdated information?

Our protagonist in the beginning wears a set of lenses that he or she is unaware no longer work. Maybe these lenses did work in the beginning, but life has changed.

Perhaps their lenses never worked at all but the character has no basis for comparison so is unaware of their myopic viewpoint. Are they wearing Mom or Dad’s glasses?

Remember, Old Motives are ‘Comfortable‘

Meaning our characters shouldn’t relinquish them easily. Remember, our characters strongly believe their vision/motive is correct, and will expend a lot of energy defending their position.

Alas, we as Author God know what’s best. Our characters are suffering the headaches, strain and fatigue and keep running into people, walls and falling over the coffee tables because their lenses are flawed.

Meanwhile, they blame everyone else, especially the cat, and are oblivious to the actual cause of their discomfort.

The core plot problem is what will reveal that the old lenses are flawed and grind new and corrected lenses that finally reveal the clear picture and alleviate the strain.

As our characters grow, the lenses change and the motive should change in accordance. This is what morphs a plain old MC (main character) into a hero by Act Three.

A ‘Novel’ Motive

First, we’ll look at a how motive (paradigm) plays out in a standalone novel.

In Liane Moriarty’s Big Little Lies the character Madeline has a family-centered paradigm. Her worth is determined by her effectiveness as a mother and, more importantly, by how much her children ‘need her.’

Her identity as a ‘good mother’ is the motive that underpins every decision she makes.

But what happens to her identity when her children reach an age that they no longer require a mother in the way Madeline has defined? How much she’s needed.

Our children should always need us (parents), but not in the same way. If Madeline’s children still need her in the same ways and to the same degree they did before starting preschool?

Um…Norman Bates anyone?

Yet, readers can relate to Madeline’s pain, to the loss and loneliness that goes with this transition inherent to parenthood. It’s what makes the story interesting and keeps readers vested.

Motive in Connected Series

Well-written series hinge on changing paradigms and maturing motives. For the character (or cast of characters) to triumph in the end, they must grow increasingly self-aware. As the world changes, the characters should also change and evolve.

This is perhaps simpler to see in a connected series like Harry Potter. Obviously, as Harry and team grow older, wiser, and stronger the challenges become increasingly difficult.

Each book prepares Harry (and allies) for the next leg of the adventure, a leg they would not otherwise be strong enough to complete.

Harry and pals would fail if directly pitted against Voldemort in Book One. Thus, the series acts as a gauntlet to strengthen the characters, reveal their flaws, correct their vision, galvanize the team and clarify the core motive for WHY they want to win. Victory is meaningless if done for the wrong reasons.

Motive in a ‘Character Connected’ Series

In what I call a ‘character connected’ or ‘disconnected’ series, the books aren’t linked together by a core plot problem. The ‘disconnected series’ is linked via a character or cast of characters.

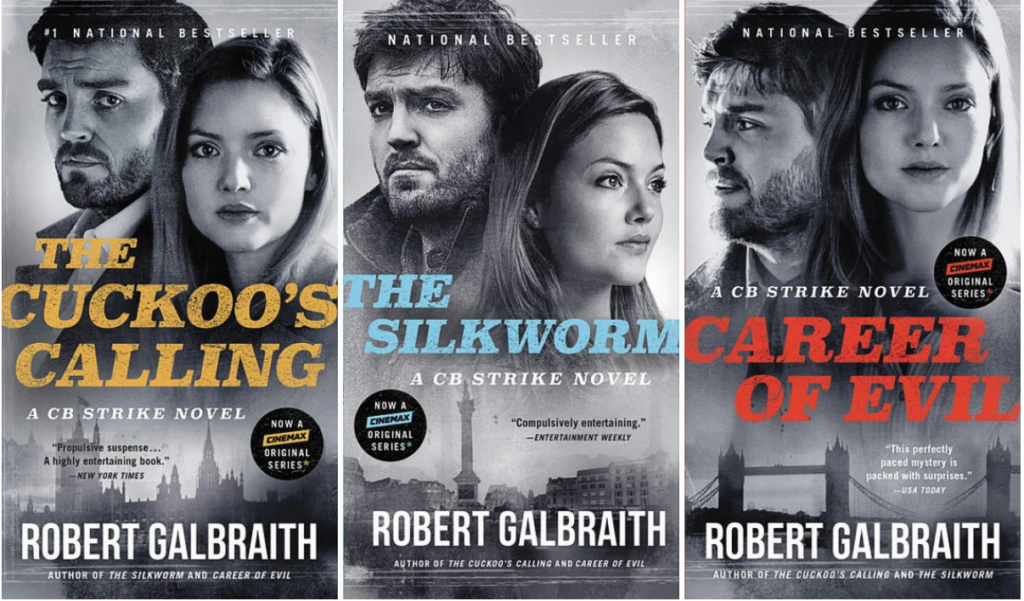

Detective novels, spy books, and thrillers are popular choices for ‘disconnected series.’ It won’t utterly confuse a reader to pick up Book Four in the Cormoran Strike detective series, but it very well could inspire readers to go back to the beginning and start at Book One.

***This is what happened with me. I read Career of Evil then went back to the beginning to find out what I’d missed.

Each book can be read independently, but adding in character arc (maturing motive) is a great way to get readers addicted to reading ALL the books.

Motive: Strike a Chord with the Reader

Robert Galbraith’s Cormoran Strike detective series is an excellent example of the character development I’m referring to. I’m absurdly addicted to this series and have read each of the books at least three times.

We meet Cormoran Strike in The Cuckoo’s Calling and learn that he’s a wounded war hero missing a leg as well as his purpose. He’s opened a private detective agency in hopes he can put his military SIB (Special Investigations Bureau) skills to use in the private sector.

We quickly learn that losing his leg in Afghanistan has taken a toll on Cormoran that goes far beyond the physical pain and frustrating limitations that go part and parcel with being disabled.

The injury has left him vulnerable, defensive and his self-worth is at all all time low (rendering him what I would call a male victim of domestic violence).

When a temp agency mistakenly sends the naive and yet deceptively tough Robin Ellacot as a personal assistant, Cormoran doesn’t have the heart to send her away.

Even though he can’t really afford to pay her long-term, and doesn’t believe he needs her help, he agrees to let her stay a week…and that week just never ends.

Motive & Character Arc

When Robin meets Cormoran, he has (literally) just extracted himself from an extremely abusive relationship (physical, emotional, and psychological). He’s hit an all-time emotional low and has no idea how to make the fledgling agency successful.

He only knows he must succeed because his identity IS the agency and if the agency fails then he, by default, is a failure as well. Robin might not have been what he ordered, but she’s definitely what he (and the agency) needed.

And vice versa. Robin mirrors Strike in more ways than either of them realizes and both characters possess depths that only a series could properly plumb.

Though each book is a different mystery, what hooked me was the characters. With every book, every defeat, triumph, near-death experience, how the characters view themselves, their world, what they want and their personal and collective motives evolve.

After four books, I’m more interested in seeing how the characters grow than I am about solving whatever mystery comes next (though I DO love a great mystery and Galbraith delivers).

Flawed Vision & Fractured Motives

When writing a novel (or a series) we must design the core story problem in such a ways that it forces change. Change is what keeps the audience interested.

Ever met a guy who never ‘grew up’ past college? He still wears what was cool in 1998 and hangs out at college bars and is utterly oblivious to how creepy he is?

That’s what happens in a series where the characters don’t ever change.

They’re the weird thirty-five year old at the fraternity mixer…and no one wants to talk to that dude book.

In a strong series, our characters must eventually realize that what they believed to be true actually was an illusion, inherently flawed, or even was once true but has changed.

Story is the crucible that reveals distorted motive(s), whether the book is a standalone or a series.

In the standalone novel Big, Little Lies, Madeline gets tossed through the parenting wringer. Her motive (in the beginning) is well intended, but her children have outgrown needing that sort of a mother…meaning she needs to ‘update’ what it means to be a ‘good mom.’

In the Cormoran Strike series, every case forces both Cormoran and Robin to face their ugly pasts. They can’t keep running away and must address the false guilt, false shame, and poisonous relationships lest there be life and death consequences.

The motive for what they do and why changes as they mature and grow closer as friends and business partners.

Motive Makes Man

Ultimately, paradigm changes everything because it’s tethered to motive. For instance, we could have a simple plot goal—throw Grandma a party for her 100th birthday.

Now look at the cast of characters. We could have the family-centered, achievement-centered, money-centered, love-centered, and work-centered character throw the party, and all would have unique strengths and weaknesses.

We could take this simple objective—throw a 100th birthday party—and have infinite variations on story because of the characters. Pick one or use ALL and watch the fireworks.

Motive points out where a character is most likely to trip, but also highlights the direction the character needs to grow. It’s this additional psychological layering that can make even a simple story deceptively complex.

Like stepping into a puddle and falling into the center of the Earth. THIS is how we can keep our writing fresh. It’s also a great way to keep surprising audiences book after book.

For more on how to create complex characters…

I had to move my new character class to this coming Tuesday, October 1st because I lost my voice this week 🙁 . But, it’s BACK!

Anyway, I’ve created a brand new class. It’s very ambitious. We’ll cover a lot, but I’m excited to teach on one of my favorite topics.

The Art of Character: Writing Characters for a SERIES

OCTOBER 1st! THIS COMING TUESDAY! Use Binge10 for $10 off.

How do we create characters that readers will fall in love with, characters strong enough to go the distance? Find out in this THREE-HOUR class that also comes with detailed notes and a character-building template. Again, use Binge10 for $10 off.

This class dovetails with my previous class:

Bring on the Binge: How to Plot and Write a Series (ON DEMAND). Use Binge10 for $10 off.

Need some help with platform and branding?

RESCHEDULED: Spilling the TEA: Blogging for Authors

THIS MONDAY, September 30th. Blogging is a powerful way to build an author brand and also make a great income doing what we love…writing. Use Tea10 for $10 off.

Branding: WHEN YOUR NAME ALONE Can Sell (ON DEMAND)

Use brand10 for $10 off.

Come join all the nerdy fun! See y’all in class!

9 comments

3 pings

Skip to comment form

EXCELLENT. Without change, that MC or whomever is involved grows tiresome. Without a worthy opponent (or a group), bleh. I have read stereotypical bad guys which turns me off. I have read (and written… ) stick figures, those who don’t deserve to live. So… therefore… change. For bad or worse. One is a bad person who has a revelation that they don’t want to be bad. They hate that person in their life who is a picture (not of paragon, mind you) who seems perfect. Motives count. Obstacles must be real. For main characters at the very least.

For me? If I can’t recall the names of the title OR MCs I end up picking it up again and eventually realize that I have read it before. I want to remember them. I want MY characters to be etched into the brains of others. I want my work to be meaningful, relevant to the readers. And yes, I want to get paid. But not for trashy work.

oooooohhhhhmmmmmm…. going back for a second read, just to enjoy the logic ride! Great great post — exceptional, actually.

Thank you, Kristen, for never changing and always giving me something more to think about, and in a new way…

Hi Kristen, I really loved this post. Your course ‘Writing Characters for a Season’ sounds amazing. Would you make this course available for on-line? I’m in New Zealand and whilst we have great writers and teachers, we don’t have a lot of access to specific courses that run in our areas. I love the way you write and explain different elements of our craft, so I just thought I would ask….

Author

Yes, it will be available On Demand once we render the recording 😀 .

Yay! Let me know when you have that available. Thanks so much Kristen xx

Author

If you sign up for the class you automatically get the recording for free, just so you know 🙂 .

Makes sense, but how much changing can a MC do when a character series stretches for over 20 books? (I’m thinking of Sue Grafton’s alphabet series and J.D Robb’s ‘In Death’ series here) How can we keep the character interesting over 6 books or 10?

How to keep a series character fresh? Outline, outline, outline. And when you run out of outline? Outline some more, Or kill them off, retire them, have them ascend into godhood or whatever, Or begin to concentrate more on the side characters–for instance, some think Peabody should have a career beyond being Eve Dallas’ sidekick. Or that it would be fun to put Roarke into a position where he can’t help her. Or that Dallas visits that farm he bought and she finds some bodies. There is always something. 🙂

Great article! You just explained to me why the Chronicles of the Harekaiian series by Shanna Lauffey keeps my attention so well. I don’t read many series but this one grabbed me and has held on through 9 books now.

[…] Plot moves the story, but it isn’t the whole story. Janice Hardy warns don’t let the plot hijack our story and explains why your plot isn’t working, but Kristen Lamb suggests that motive is the real force behind page turners. […]

[…] I’ve long talked about the importance of a character’s motivation for creating an engaging novel, so naturally I was excited to read author Kristen Lamb’s very exhaustive post on characters and motives. […]

[…] Kristen Lamb’s blog – https://authorkristenlamb.com/2019/09/motive-stories-readers/ […]